Reference: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rock-climbing_equipment

Quickdraw – Ekspres #

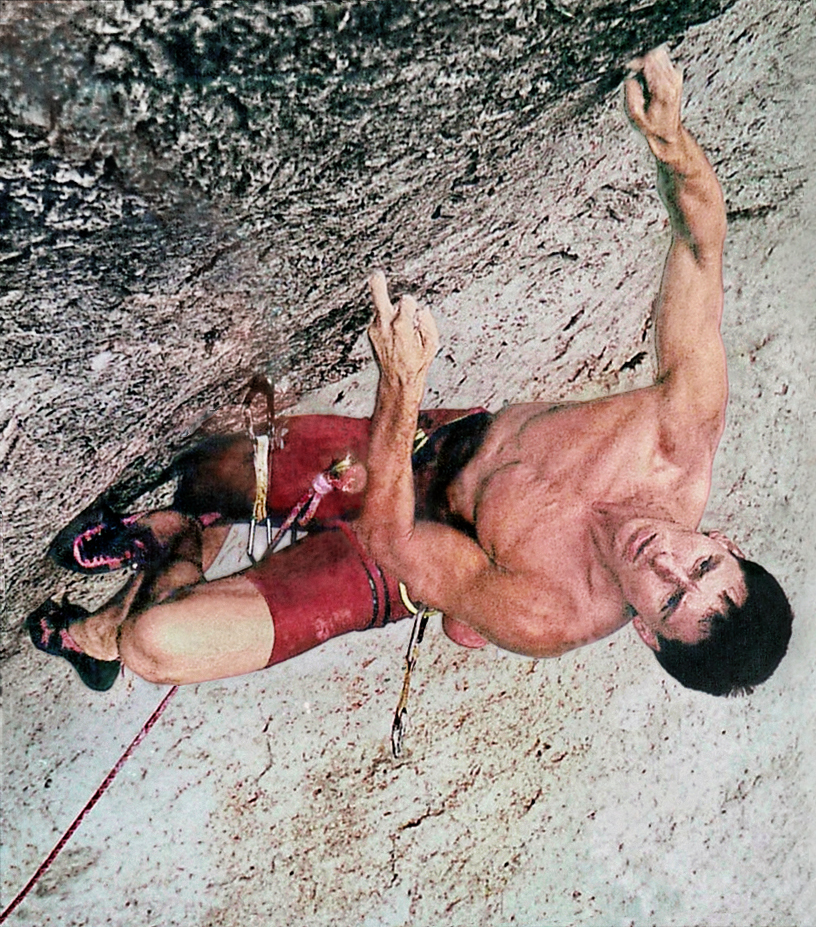

Quickdraws (often referred to as “draws”) are used by climbers to connect ropes to bolt anchors, or to other traditional protection, allowing the rope to move through the anchoring system with minimal friction. A quickdraw consists of two non-locking carabiners connected together by a short, pre-sewn loop of webbing. Alternatively, and quite regularly, the pre-sewn webbing is replaced by a sling of the above-mentioned dyneema/nylon webbing. This is usually of a 60 cm loop and can be tripled over between the carabiners to form a 20 cm loop. Then when more length is needed the sling can be turned back into a 60 cm loop offering more versatility than a pre-sewn loop. Carabiners used for clipping into the protection generally have a straight gate, decreasing the possibility of the carabiner accidentally unclipping from the protection. The carabiner into which the rope is clipped often has a bent gate, so that clipping the rope into this carabiner can be done quickly and easily. Quickdraws are also frequently used in indoor lead climbing. The quickdraw may be pre-attached to the wall. When a climber ascends the wall, (s)he must clip the rope through the quickdraw in order to maintain safety. The safest, easiest and most effective place to clip into a quickdraw is when it is at waist height

Harness – Emniyet Kemeri #

A harness is a system used for connecting the rope to the climber. There are two loops at the front of the harness where the climber ties into the rope at the working end using a figure-eight knot. Most harnesses used in climbing are preconstructed and are worn around the pelvis and hips, although other types are used occasionally.

Different types of climbing warrant particular features for harnesses. Sport climbers typically use minimalistic harnesses, some with sewn-on gear loops. Alpine climbers often choose lightweight harnesses, perhaps with detachable leg loops. Big Wall climbers generally prefer padded waist belts and leg loops. There are also full body harnesses for children, whose pelvises may be too narrow to support a standard harness safely. These harnesses prevent children from falling even when inverted, and are either manufactured for children or constructed out of webbing. Some climbers use full body harnesses when there is a chance of inverting, or when carrying a heavy bag. There are also chest harnesses, which are used only in combination with a sit harness. Test results from UIAA show that chest harnesses do not put more impact on the neck than sit harnesses, giving them the same advantages as full body harness.[6]

Apart from these harnesses, there are also caving and canyoning harnesses, which all serve different purposes. For example, a caving harness is made of tough waterproof and unpadded material, with dual attachment points. Releasing the maillon from these attachment points loosens the harness quickly.

Canyoning harnesses are somewhat like climbing harnesses, often without the padding, but with a seat protector, making it more comfortable to rappel. These usually have a single attachment point of Dyneema.

Belay loop: The strongest point on a climbing harness; the loop to which a belay device is physically attached. The belay loop will wear more quickly if anything is tied around the belay loop such as a daisy chain or sling.

Belay device – Emniyet alma aleti #

Belay devices are mechanical friction brake devices used to control a rope when belaying. Their main purpose is to allow the rope to be locked off with minimal effort to arrest a climber’s fall. Multiple kinds of belay devices exist, such as tubers (for example the Black Diamond ATC) or active assisted-braking devices (for example the Petzl Grigri), some of which may additionally be used as descenders for controlled descent on a rope, as in abseiling or rappelling.

If a belay device is lost or damaged, a Munter hitch on a carabiner can be used as an improvised passive belay device.

Sling – Perlon #

A sling or runner is an item of climbing equipment consisting of a tied or sewn loop of webbing that can be wrapped around sections of rock, hitched (tied) to other pieces of equipment or even tied directly to a tensioned line using a prusik knot, for anchor extension (to reduce rope drag and for other purposes), equalisation, or climbing the rope.

Carabiner – Karabina #

Carabiners are metal loops with spring-loaded gates (openings), used as connectors. Once made primarily from steel, almost all carabiners for recreational climbing are now made from a lightweight but very strong aluminum alloy. Steel carabiners are much heavier, but harder wearing, and therefore are often used by instructors when working with groups.

Carabiners exist in various forms; the shape of the carabiner and the type of gate varies according to the use for which it is intended. There are two major varieties: locking and non-locking carabiners. Locking carabiners offer a method of preventing the gate from opening when in use. Locking carabiners are used for important connections, such as at the anchor point or a belay device. There are several different types of locking carabiners, including a twist-lock and a thread-lock. Twist-lock carabiners are commonly referred to as “auto-locking carabiners” due to their spring-loaded locking mechanism. Non-locking carabiners are commonly found as a component of quickdraws.

Carabiners are made with many different types of gates including wire-gate, bent-gate, and straight-gate. The different gates have different strengths and uses. Most locking carabiners utilize a straight-gate. Bent-gate and wire-gate carabiners are usually found on the rope-end of quickdraws, as they facilitate easier rope clipping than straight-gate carabiners.

Carabiners are also known by many slang names including biner (pronounced beaner) or Krab.

The first climber who used a carabiner for climbing was German climber Otto Herzog.[5]

The Maillon (or Maillon Rapide) performs a similar function to a carabiner but instead of a hinge, it has an internally threaded sleeve engaging with threads on each end of the link, and is available in various shapes and sizes. They are very strong but more difficult to open, either deliberately or accidentally, so are used for links which do not need to be released during normal use, such as the center of a harness.

Rope – İp #

Climbing ropes are typically of kernmantle construction, consisting of a core (kern) of long twisted fibres and an outer sheath (mantle) of woven coloured fibres. The core provides about 70% of the tensile strength,[2] while the sheath is a durable layer that protects the core and gives the rope desirable handling characteristics.

Ropes used for climbing can be divided into two classes: dynamic ropes and low elongation ropes (sometimes called “static” ropes). Dynamic ropes are designed to absorb the energy of a falling climber, and are usually used as belaying ropes. When a climber falls, the rope stretches, reducing the maximum force experienced by the climber, their belayer, and equipment. Low elongation ropes stretch much less, and are usually used in anchoring systems. They are also used for abseiling (rappelling) and as fixed ropes climbed with ascenders.

Modern webbing or “tape” is made of nylon or Spectra/Dyneema, or a combination of the two. Climbing-specific nylon webbing is generally tubular webbing, that is, it is a tube of nylon pressed flat. It is very strong, generally rated in excess of 9 kN (2,000 lbf). Dyneema is even stronger, often rated above 20 kN (4,500 lbf) and as high as 27 kN (6,100 lbf).[3] In 2010, UK-based DMM performed fall factor 1 and 2 tests on various Dyneema and Nylon webbings, showing Dyneema slings can fail even under 60 cm falls. Tying knots in Dyneema webbing was proven to have reduced the total amount of supported force by as much as half.[4]

When webbing is sewn or tied together at the ends, it becomes a sling or runner, and if you clip a carabiner to each end of the sling, you have a quickdraw. These loops are made one of two ways—sewn (using reinforced stitching) or tied. Both ways of forming runners have advantages and drawbacks, and it is for the individual climber to choose which to use. Generally speaking, most climbers carry a few of both types. It is also important to note that only nylon can be safely knotted into a runner (usually using a water knot or beer knot), Dyneema is always sewn because the fibers are too slippery to hold a knot under weight.

Webbing has many uses such as:

- Extending the distance between protection and a tie-in point.

- An anchor around a tree or rock.

- An anchor extension or equalization.

- Makeshift harnesses.

- Carrying equipment (clipped to a sling worn over the shoulder).

- Protecting a rope that hangs over a sharp edge (tubular webbing).

Helmet – Kask #

The climbing helmet is a piece of safety equipment that primarily protects the skull against falling debris (such as rocks or dropped pieces of protection) and impact forces during a fall. For example, if a lead climber allows the rope to wrap behind an ankle, a fall can flip the climber over and consequently impact the back of the head. Furthermore, any effects of pendulum from a fall that have not been compensated for by the belayer may also result in head injury to the climber. The risk of head injury to a falling climber can be further significantly mitigated by falling correctly.

Climbers may decide whether to wear a helmet based on a number of factors such as the type of climb being attempted, concerns about weight, reductions in agility, added encumbrances, or simple vanity. Additionally, there is less incentive to wear a helmet in artificial climbing environments like indoor climbing walls (where routes and holds are regularly maintained) than on natural multi-pitch routes or ice climbing routes (where falling rocks and/or ice are likely).

Climbing shoes – Tırmanış ayakkabısı #

Specifically designed foot wear is usually worn for climbing. To increase the grip of the foot on a climbing wall or rock face due to friction, the shoe is soled with a vulcanized rubber layer. Usually, shoes are only a few millimetres thick and fit very snugly around the foot. Stiffer shoes are used for “edging”, more compliant ones for “smearing”. Some have foam padding on the heel to make descents and rappels more comfortable. Climbing shoes can be re-soled which decreases the frequency that shoes need to be replaced.

Chalk – Magnezyum Tozu #

Chalk Bag – Toz Torbası #

Chalk is used by nearly all climbers to absorb problematic moisture, often sweat, on the hands. Typically, chalk is stored as a loose powder in a special chalk bag designed to prevent spillage, most often closed with a drawstring. This chalk bag is then hung by a carabiner from the climbing harness or from a simple belt worn around the climber’s waist . This allows the climber to re-chalk during the climb with minimal interruption or effort. To prevent excess chalking (which can actually decrease friction), some climbers will store their chalk in a chalk ball, which is then kept in the chalk bag. A chalk ball is a very fine, mesh sack that allows chalk release with minimum leakage when squeezed so that the climber can control the amount of chalk on the hands.

Chalk is most frequently white, and the repeated use of holds by freshly-chalked hands leads to chalky build-up. While this isn’t a concern in an indoor gym setting, white chalk build-up on the natural rock of outdoor climbs is considered to be an eyesore at best, and many consider it a legitimate environmental/conservation concern. In the United States, the Bureau of Land Management advocates the use of chalk that matches the color of the native rock.[14] Several popular climbing areas, like Arches National Park in Utah, have banned white chalk, instead allowing the use of rock-colored chalk. A handful of companies make colored chalk or a chalk substitute designed to comply with these environmental conservation measures. Garden of the Gods in Colorado has gone further, banning the use of all chalk and chalk substitutes outright.

Beta #

(Belirli bir tırmanış rotasının nasıl başarıyla tamamlanacağına ilişkin tavsiyeler, ipuçları veya genel bilgiler)

Advice, tips, or general information on how to successfully complete (or protect) a particular climbing route, boulder problem, or crux sequence. Some climbing purists believe that obtaining beta prior to attempting a route “taints” an ascent.

Crux – Bir rotanın en zor (kilit) bölümü #

A crux in climbing, mountaineering and high mountain touring is the most difficult section of a route, or the place where the greatest danger exists. In sport climbing and bouldering, the most technically challenging point in the climb is also called the crux section.[1] In describing a climbing route using a topo, cruces (or cruxes) are usually shown with a key symbol.

The grade of a climbing route is based on the technical difficulty of the crux (e.g. 8a (5.13b) in the sport climbing system, or V13 (8B) in the bouldering system), and for traditional climbing routes, an additional grade is used for the risk of personal injury to a climber of a fall at the crux (e.g. the British E-grade system). That means the rest of the route might be considerably easier, however, a route may comprise several cruces of equal difficulty, or simply be a route of a very consistent level of difficulty with no sections that stand out as harder than the rest.

In planning a route it is important to know how far it is before the crux is reached, because cruces (or cruxes),[2] can only be overcome with sufficient reserves of strength.[3] Sport climbers have come to use a kneebar to rest before, or immediately after, a crux; they can also continually practice a crux using top roping.